the time i realised i wouldn’t walk again

This is a new story, a continuing story, because I’m still figuring out how to write about it. I think it’s why I started writing so many stories from when I could walk without aid.

It started in 2022 — I was 39. One morning, I stepped out of bed and collapsed from the pain. There wasn’t any warning, and I had no idea what to do.

For the meantime, I bought a cane and enjoyed that while I kept about my normal life. I loved to wear a suit, and I played music almost every week in Paris. The cane just fit with the outlaw country or blues I liked to sing.

I kept going to doctor after doctor to figure out what was wrong. Each one had a different answer. Most claimed I was fine and just needed to exercise more. I had a few x-rays, but apparently none showed what was happening.

The pain grew stronger, and finally an X-ray showed what was happening. The ball in my hip joint was falling apart, and it had a pyramid-like spike sticking into my tendons. I would need a new hip.

This was good news to me at first — a prosthetic hip seemed like a simple procedure and I’d be walking in no time. After all, I lived in France and had decent health care for the first time in my life.

But there was something worse coming.

One day in January 2023, I woke up looking jaundiced. I didn’t notice until my friends Rico and Isa commented on it when they came to accompany me to a doctor. The doctor took one look and said I had to go to the emergency room.

Rico and Isa raced me to l’Hôpital Saint-Antoine where I waited in the emergency room for some 8 hours. I watched overdoses come in, car accident victims, people in handcuffs. And after many hours, they gave me a bed for a night, in a room full of people. They all groaned through the night.

I curled up with my arms threaded through my backpack straps, the same way I used to sleep while living on the street. I barely slept.

The next day was the last day I remembered for a while. They checked me into the ICU with septic shock in nearly all my organs. Some unknown infection was eating away at me. I had to be put in a coma and then process all the medication through a damaged liver and kidneys. It almost hit my heart, and I learned later that I almost didn’t make it.

Some of this, I was later told, was from drinking too much. I knew I should have been cutting back for years, but this kind of affect never occurred to me. Most of my friends hadn’t gone through this, and they still partied!

But at the hospital, this was far from my mind. All I remember is that I was being treated in various facilities in the snow. Sometimes it was in China, sometimes Korea, sometimes a Scandinavian village. I had all kinds of adventures: one set in a village of witches, one with a series of murders, one on a moving surgery train. All hallucinations. I made attempts to escape to get back to Paris, friends of mine appearing to help me and then leaving…

It was so real that I can still feel each storyline and every face. Julie had to work with me over days to convince me I had never left Paris, showing me with maps on her phone. I sometimes answered a nurse in Mandarin, only to hear, “Français, s’il vous plaît!”

Six months later, my memory fried and my body atrophied, I had to work on walking again. I hadn’t received a prosthetic. They were too worried about the infection — it would be another year before that came.

I worked hard on my muscles and strengthening my heart through slow calisthenics. And I tried working again, as a long-distance teacher for a tech school in Rennes. The six-month absence had destroyed my savings, and salaries weren’t great for either of us in Paris.

We had to leave our apartment and head a little farther from the city on our budget. We ended up in St. Denis, known for being shadier, with more drugs and violence. Neither of us experienced or saw that, though. And I started drinking again, having trouble with the pain and the stress of moving.

Finally, I was tired and so was Julie. I volunteered to enter a rehab program to get myself healthy enough for more surgery. This took a few tries, but I quit smoking and drinking for the first time in my life. (That’s a whole other story.) After a few months, I was ready, and we found a surgeon at a different hospital. I was getting the prosthetic and going to be walking again.

That worked for a little while — I could walk up and down stairs, sometimes without a cane, I could hobble around town. I still needed a wheelchair if we were going anywhere far, because I was still recovering. My French was getting better and better from so much time spent in the hospital system.

But the next cycle started. We moved to Switzerland, and the prosthetic immediately became infected. It was taken out, cleaned, and then I would get another prosthetic. Then it would almost immediately dislocate. Sometimes this required surgery to get it back into place. Then another infection would start.

This cycle went on and on, and my first 8 months in Switzerland were spent more in the hospital than in our home. I rarely had two weeks without an emergency visit or new pain and infection.

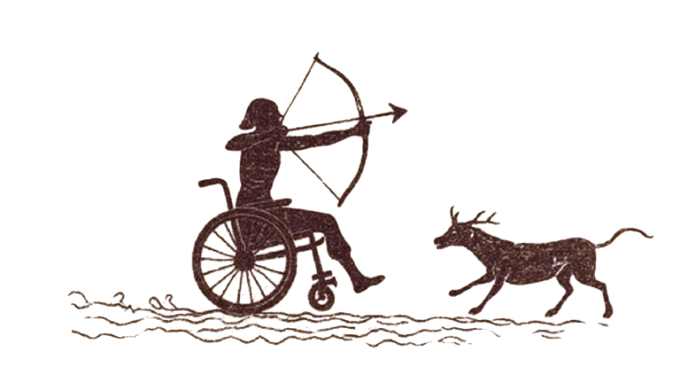

All this led to today — a long, boring cycle of surgeries and relearning to walk each time. And now, they’re about to give up on the infection and I’ll be keeping the wheelchair. I have one more chance for a prosthetic, but I’m doubtful given all the failures. And even if it works, my mobility would be “significantly reduced”.

There won’t be any more running up the middle fork of the Gila River to spend long days at the hot springs. There won’t be more carrying a heavy bag into the desert to spend weeks looking for gold or fossils. I don’t even know if I’ll be able to dance again.

So I’ve been thinking of stories when I used to run, walk, or ride anywhere. I tried my first electric-powered chair, which is fun. But I catch myself staring when people jump up the stairs, two steps at a time.

If you made it this far, thank you for listening to my story. This is the first time I’ve tried to put it into words as a way of facing my new life situation. I’m not giving up on adventures — I still plan to travel, kayak, and play music as well as I can. At a slower speed. Sober. Paying a lot more attention to how people see someone who goes by in a wheelchair. Thinking a lot more about accessibility and my place in the world.

I spent my first forty years walking and running. For the next forty, I’ll be rolling towards all the same goals, and a few new ones at that. Allonz-y.