reframing my story

Strangely, it never occurred to me, after losing my leg, to feel “Why me?” Perhaps this is my natural existentialism that tends to think every occurrence in life has equal odds. You will either die today or you won’t. I’ll spend tonight partying with Rihanna or I won’t. 50/50 odds.

I realize that isn’t how probabilities work. I’m well-grounded in statistical mathematics and use large data sets every day as a programmer. It’s more of a philosophy for accepting a bizarre world with all its twists and turns and pleasures.

This strange relationship with probability shaped how I moved through the world. If everything was equally possible, then difficulty wasn’t something to avoid - it was just another path.

Now, it becomes easier to imagine instead the question: “Why not me?” This shift in perspective didn’t happen quickly. I’ve been thinking about this for nearly three years in the hospital. When I looked back over my life, I started to feel a pattern. I’ve thrown myself into uncomfortable situations just to see if I make it out on top.

There are a few stories that stand out to me that illustrate these patterns.

I remember summers as a teenager in New Hampshire, standing in our overgrown yard with a rusted scythe all by myself to cut the grass. My parents were into traditional work and wouldn’t get me a lawn mower. My arms would be on fire after ten minutes, my back ached, and I had barely made a dent in the grass.

I wanted to quit, to argue (I definitely argued). There had to be an easier way in the 1990s. But a mixture of obedience and pride kept me swinging that blade, hour after hour, day after day, until the yard was cleaned and I had to start at the beginning again the next day, where it had already grown back. At the time, it felt like punishment. Now I recognize it as one of the first lessons in pushing through when everything in your body says stop.

The day I was excommunicated is another memory I’ll never forget. I had reached my breaking point in following petty right-wing rules that made no logical or useful sense to me, and though it was my whole world, the elders of the church sat and signed a letter “handing me directly over to Satan.” I was not even allowed to try to attend another church or they would track me down and make sure the pastor knew how much “trouble” I was.

For months, then, I felt isolated, stepping into the dark, having to rebuild my moral compass without the Christian church. Family members wouldn’t talk to me. Men from the church would search for me on the streets, trying to find me and save me. I wrote for Christian magazines but had to stop because I no longer believed what I was writing.

Somehow I didn’t break. Instead, I learned to build new kinds of strength. I had to define my own ethical system and I chose kindness and empathy at its center - not that I didn’t make a boatload of mistakes along the way. It helped that, in general, diverse communities are kinder than semi-cultish rural Idaho versions of Christianity.

And animals became my teachers in ways I didn’t expect. When you’re caring for creatures who can’t tell you what’s wrong, you learn to read other signals. You notice how breathing signals distress, the way pain changes posture, how illness shows itself in a thousand small signs before it becomes obvious.

I spent hours watching abused animals, held a wolf in my arms as she died, learning to see how one favored her left front leg, how she held her head differently when the pain flared. Giving cats their injections. Arguing with a fox who kept stealing my cigarettes. Each animal taught me that bodies communicate constantly - you just have to know how to listen.

But the thing was, those animals were always there, always living, patient. I saw how to sit quietly with discomfort, how to offer comfort without expecting gratitude, how to respect the dignity of a creature who was having trouble but still fighting.

I’ve mentioned this before in my story about Hurricane Katrina (the day the house exploded). l learned first aid, CPR, and disaster relief, and kept my certifications renewed. The experience helped me to understand trauma, triage, and how to function when everything falls apart. Skills I thought were about helping others but turned out to be preparation for helping myself.

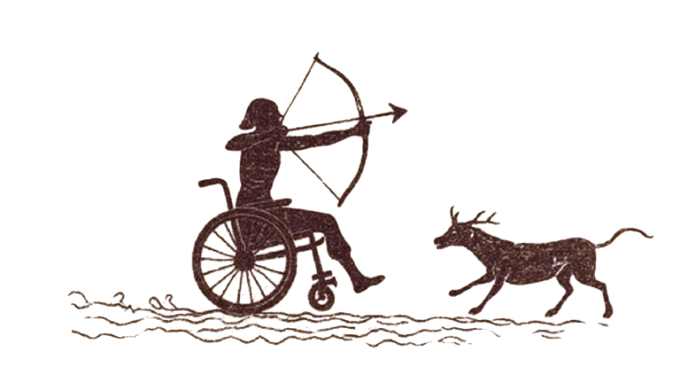

Writing and talking with Julie about these stories led to my major insight: I am reframing my own story, and now see all my stories as training for what I’m going through right now with my own pain and disability. I think about it when I struggle to wake up each morning and when I spend hours a day on physical therapy and building strength.

All these experiences in the margins of society taught me something that should have been more obvious: the world will often tell you that you don’t belong, that you’re somehow less than “normal”. Whether it’s because of your beliefs or your body, society has ways of making you feel like an outsider. But I had already been an outsider for so long, I had learned resilience and kindness.

Now, those lessons come back. When people see my disability first and me second, I remember those animals who were so much more than their pain or limits. I see everything that built a solid stubborn streak in me.

“Why not me?” has effectively become the statement “Of course I had to be disabled - it was the logical next step in my life story.” As if the storyteller in me wouldn’t have it any other way.

As I continue, as I enter into advocacy for others with disabilities, as it seeps into every part of my life, that thought keeps me strong. I was meant for this.

Or whatever, because there was always a 50/50 chance.