that one time i never stopped loving the internet

For the longest time, since I was a child, I loved tinkering with computers — taking them apart and rebuilding them, then using childish fantasies to make MS-DOS answer me if I asked specific questions. My private choose-your-own-adventure AI assistant. Sort of.

I think it was a child’s answer to looking for a computer friend, which I now consider cute. I could have my own “Short Circuit” robot friend (“Number 5 Alive!”) or, for a more modern reference, Baymax from “Big Hero 6.” Maybe even Bumblebee. Those movies still resonate with me.

My parents homeschooled me, often isolating me from peers. I would get in trouble with my parents if I tried to make friends or play sports with the neighbors. There were many books I could not read, and I had no TV to watch, to protect my young mind from seeing or reading about any sin or alternative philosophy. Most Americans will recognize the type, where it is as sinful to read about Buddhism as it was to talk to a girl in a tight shirt.

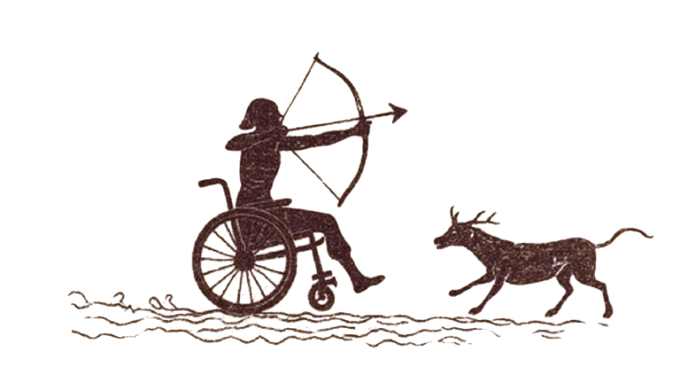

So the years went on, and my isolation continued; MS-DOS remained a reliable companion. But I began to focus more on studying mathematics, reading classic literature, and living outside. We had moved into a more rural neighborhood, and I spent a lot of time exploring, crafting “weapons”, learning how animals acted and how to track them, reading and collecting medicinal plants, or going on my own fantasy adventures. As I consider this now, I was still looking for connections and a specific type of “conversation” and “language” I could have with nature.

The woods offered a temporary freedom, but eventually, I felt the limits of my borders again. And this time, I had the internet to play with. The allure of using computers to communicate with people beyond my books and neighborhood was irresistible. It was a way to escape my religious ties as much as the woods were… My parents could monitor TVs or books, but they were also learning to use the internet, so I felt on equal ground. If I could hide, I could access all the information I was curious about.

I started by finding ways to cover my tracks on early web browsers. I found The Anarchist Cookbook, read about Kevin Mitnick or Cap’n Crunch, two famous old hackers, and read all their tricks. I even shoplifted a digital recorder from Radio Shack, using an MS-DOS program to replicate the exact frequencies to pay a payphone. That was how to do it: find the frequency of each coin and play it into the mouthpiece. Alas, I could not make that work because the phone companies had already figured out how to block that. I had to figure out new ways of connecting online.

Shortly later, I bought a Compaq Luggable from my dad — something similar to this linked photo.

But that wasn’t enough to use the internet, so I still needed more. I raided a telephone company truck to get wires and tools while they worked on a house. I stole a modem and some cables. To be clear, I consider this wrong. I knew it was wrong even then.

But in my mind, I thought it was a way of adapting in a right-wing, isolationist, militia-friendly way of growing up. There was a sort of self-myth I used to justify this: if the Christian world would stifle my curiosity, I was within my rights to learn and communicate however I could, without harming others.

I would plug into neighbours’ phone lines, dressed in camouflage that my parents bought me, or with money I earned by mowing lawns. I would hide in the bushes with my computer, covered with camo nets, and connect slowly to the internet. I had a stolen phone from a thrift store and hid it in my massive used coat.

Now I was getting in, and now I was finding actual information. Stuff I couldn’t even find in the library. Guess what I did with this knowledge and set up? Porn? Cat pictures? Study more Klingon?

Nope. I connected with people. I called random payphones from a list of cities in the USA and Germany. I would wait until someone answered and ask who they were. I asked about the weather, their day, or something random. It was usually an awkward but well-meaning conversation that, if memory serves, would go like this:

Stranger in Munich/Rotterdam/Brussels after 15 rings: “Hallo?” Me: “Hello! How are you today?” Stranger: “Um… Good, who is this?” Me: “I’m calling a list of payphones to say hi.” Stranger: “Ah.” Me: “So… how is the weather there?” Stranger: “It is raining a little.” Me: “…” Stranger: “… I must go to work now, ya?” Me: “Have a wonderful day!” Him: “You too.”

You can see my conversation skills have always been second to none.

This was around 1994–1996. Payphones were widely available around the cities, and people occasionally answered them. I had no idea who I was talking to, sitting in a bush in rural Missouri — in full camo — with stolen equipment and a list of payphones I found on IRC channels. I called people in South America. I called people in every major city.

Calling a payphone might not work, or someone might answer. I could understand some people, but not others. I can only imagine the long-distance phone bills in my neighborhood. This countered my rule about “harm none,” and I still feel guilty about it. At the time, it was a necessary evil to me.

I was always looking for more connections, never thinking of the consequences. I tried to share my newfound knowledge with other kids my age. They immediately told their parents, who told mine.

That went badly for me — it was back when my parents would make you pick a stick from the woods for them to use on you for corporal punishment.

And I’m pretty sure they knew I was shoplifting from Radio Shack, but the random employees didn’t care, or perhaps saw the company’s future and enjoyed that some nerdy kid was keeping the flame alive. I wonder who they were.

This became a lifetime of finding connections — friends, dates, work, a bus stop, or random people with a story. I remain optimistic about the internet — some want to connect but don’t have the technology until they build it. Maybe someone like me, hiding in bushes or the library, telling their story on some forum. Perhaps someone who has a block on their country’s Internet. Or just someone who finds it easier to gain confidence their way. It’s why the useless big-box playgrounds of Twitter and Facebook were so easy to escape, as we created and learned new ways to stay connected.

It’s why I still talk to friends from 20 years ago that I’ve still never even met. It’s why I value the smallest interactions in the real world. I try to be polite and kind to everyone around me. And perhaps that’s the best thing that could have happened from a childhood spent being told that the world was evil and I should avoid it so it didn’t infect me.